Demystifying “In, Out, Make”: The most common calling positions #

In this section, we’ll start to build the vocabulary and skills you’ll need to call longer and more complicated touches. When touches are longer than a few leads, it quickly becomes tiresome to memorize a long series of “plain, bob, bob, plain, bob, plain…”. To fix that problem, callers and conductors often use calling positions to help them remember where to put in the calls. We’ll first define calling positions and then tell you about some of the most common ones. In Calling It Round, we will mostly be covering methods like Plain Bob or Cambridge Surprise, which are methods with a single hunt bell, the treble. I hope to add supplements about Grandsire (a method with two hunt bells) and Stedman (a principle), so stay tuned if those interest you! Knowing this vocabulary will give you access to a much bigger number of compositions! In the next section, we’ll get down to brass tacks learning new compositions using this new vocabulary.

Courses and Calling Positions #

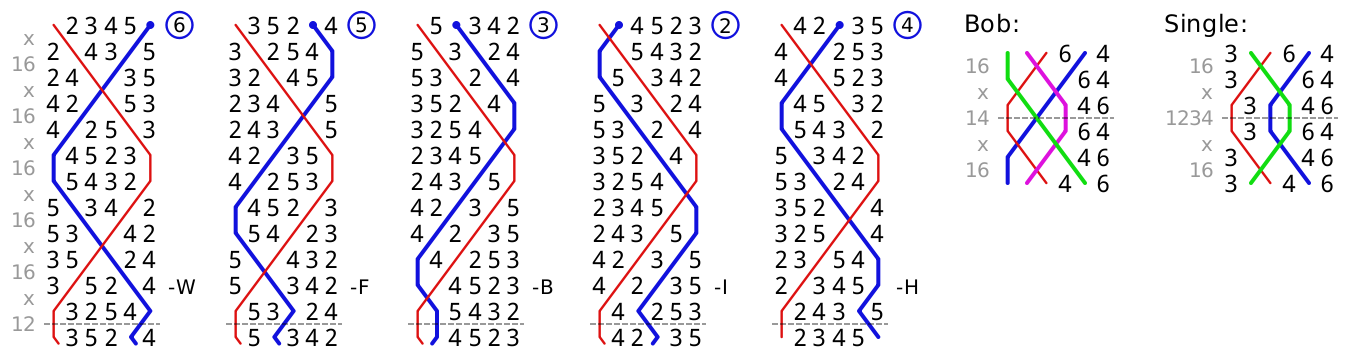

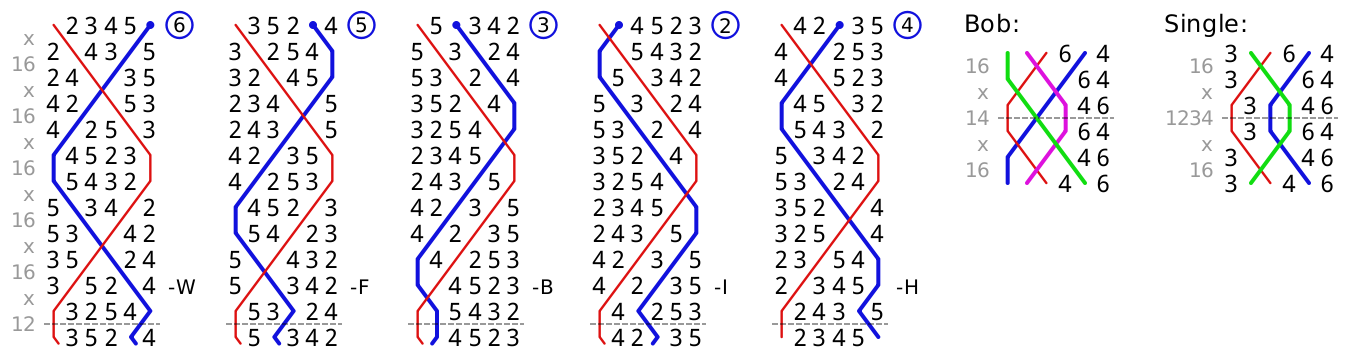

A plain course is a course of a method where there is no call at any lead end. However, callers and conductors often talk about courses which may or may not have calls in them. A course of this type starts when a tenor is in its home or natural position (in Plain Bob Minor, this is being in 6ths place at the backstroke of the lead end), and ends when the tenor has returned to its natural position. At some point, you have likely seen the plain course of a method written out like this:

You’ll probably recognize this as Plain Bob Minor; there’s a treble (red line) plain hunting, and a bunch of other bells all dodging at the lead end (except one which is making seconds). Note that the tenor starts in 6ths place at the treble’s backstroke lead during rounds, and returns to 6ths place at the treble’s final backstroke lead in rounds.

In a tiny font off to the right hand side of each lead, you can see letters pointing to a particular place in the lead. These letters are shorthand for the names of various calling positions relative to a specific observation bell. Here, the observation bell is the tenor, in blue. An observation bell is a bell that you watch while you figure out where the calls go in a composition.

A calling position is a position in the blue line (of the observation bell) where a call may be made.1 You can see that the hyphen next to the letter indicates the position in the row where the call would be made; it would then be executed at the treble’s lead. For convenience, many methods and principles have named calling positions. In the image above, five of these named calling positions are labelled: Wrong (W), Fourths (F), Before (B), In (I), and Home (H). In this section, I will always spell out the whole name, but give the common abbreviation in parentheses after. The calling positions in the diagram refer to the position that the observation bell (here, the tenor) would be in if a call were to be made. This fact can feel a bit unintuitive, because the plain course is written out such that there is a plain at every lead, but the calling positions refer to what would happen if a call were made.2 Let’s work our way through those calling positions with that in mind:

| Calling Position(s) | Abbr | Definition (with tenor as observation bell) |

|---|---|---|

| Home | H | This calling position is the one where the tenor ends up at home (the 6th bell ending up in 6th place) at the lead end if a call is made. |

| In | I | This calling position is the one where the tenor would end up running in if a call were made. |

| Out (Sometimes: Before) | O or B | This calling position is the one where the tenor would end up running out if a call were made. It is sometimes known as “Before” because it happens when the tenor is coursing before the treble. |

| Make (Sometimes: Fourths) | M3 or F | If a call is made here, the tenor will make fourths. |

| Wrong4 | W | If a call is made here, the tenor winds up in 5ths at the backstroke of the lead end (by either dodging or hunting!). More generally, if a method is being rung on a stage with n bells, the calling position where the tenor ends up at position (n-1) is called Wrong (W). For example, in Plain Bob Major, if the tenor winds up in 7 after the call, the call was made at Wrong. |

These calling positions — Home (H), In (I), Out (O), Before (B), Make (M), Fourths (F), and Wrong (W) — make up the majority of calling positions used in most compositions. Be aware that these named calling positions may change, unfortunately, from method to method (or principle), or from stage to stage. Worse, the abbreviations are not always unique; most important to be aware of is that (M) may mean either make (make fourths) or middle, which we haven’t discussed yet since it only comes up in higher stages.

With only 7 new words in your arsenal, you now have access to a huge number of compositions. For example, a great source of short touches is the Ringing World diary, a new edition of which is released each year; many compositions in the diary use only these calls, and the next section will introduce you to some of those compositions to help you get started.

Frequently Asked Questions #

What does it mean if someone asks me to “call a Wrong”? #

This phrase is often shorthand for “call a bob at the calling position Wrong”. The phrase “call a single Wrong” most often means to call a single at the Wrong.

When do I use Out vs Before? Or Make vs Fourths? #

Out and Before are two different names for the same calling position relative to the position of the observation bell; they both refer to a place in the lead where calling “bob” would lead to the observation bell running out. As a general (though not perfect) rule, methods that have a bell making seconds at the lead end use the names Before and Fourths, and methods that have plain hunt at the lead end use the names Out and Make. There are exceptions to this rule; for example, the calling positions in some doubles methods (including Plain Bob Doubles) are In, Out, and Make5 even though a bell makes seconds at the lead end. Always make sure to check you know what the calling positions mean for the method and composition you are using.

How does my understanding of calling positions change if the observation bell is not the tenor? #

As discussed above, an observation bell is the bell that you are watching (and perhaps ringing) to figure out where the calls go. In the diagram above, the tenor is the observation bell. Other bells can also serve as observation bells, but the calling position names remain the same. For example, if you are “ringing 4 as observation,” the call made at the position Home (H) will be made right before the 4 dodges into 6th place at the treble’s backstroke lead. This point is especially important to be aware of if you are hoping to call from a smaller bell.

Does this mean I can ring a composition from any bell as observation, not just the tenor? #

Yes and no. Some compositions are suitable to be rung with any bell as observation. However, most compositions are written with the tenor as observation, and often this is for good reason; the same composition with a different bell as observation may have undesirable musical qualities or other, bigger problems. If you’re planning on calling a composition in a different way to how it was set down by the composer, always check to make sure the resulting ringing will still be what you want it to be. In the Conducting section Round the Circle, I will cover this topic in more detail.

Where do I go to learn more about calling positions? #

It is likely that there is at least one ringer in your local area who is happy to talk you through all your questions. However, there are other great resources to learn more:

- Steve Coleman’s The Bob Caller’s Companion, a great general-purpose resource for those learning to call

- Tina Stoecklin and Simon Gay’s Change-Ringing on Handbells (Volume 1: Basic Techniques), another good general resource but focussed more on handbells

- John Harrison’s Glossary, especially for looking up the names or abbreviations of other calling positions

I’m sure there are many others. If you are aware of (or author of!) any other resources you’d like to make people aware of, please contact me and I will add it to this space.

Exercises #

Quiz This #

Assume all questions refer to Plain Bob Minor, with the 6 as observation bell (as in the image), unless otherwise stated.

If I make a call at In (I), the tenor will run out at the lead end.

If I make a call at Wrong (W), the tenor will be in 6ths place after the dodge.

If I make a call at Fourths (F), the tenor will make the bob.

How many calling positions are there in Plain Bob Minor?

How many calling positions are there in Plain Bob Doubles?

Compose This #

Last section, we learned a simple composition of Plain Bob Doubles that consisted of just two bobs, right next to each other. Bearing in mind that the calling positions for Plain Bob Doubles are In, Out, Make, Home, can you translate that touch into notation that uses calling positions? Remember that most compositions assume that the heaviest working bell, here the 5, is the “observation bell” to which the calls pertain. (Hint, if you get stuck: Try writing out all the changes in the touch. Note what the 5 does at each lead. What would those calling positions be called?)

Consider This #

Last section, we learned a simple lead-by-lead notation for calls. This time, we learned about calling positions (and next time, we’ll talk more about notation for compositions using calling positions). What are some pros and cons of using lead-by-lead notation instead of named calling positions? Which would you rather use to learn a very short touch? Which would you rather use to learn a quarter peal?

Notes #

This is mostly true. It is not always true for Stedman or Erin, but is true for the vast majority of commonly rung methods (and some principles); the work of the observation bell directly relates to the name of the calling position. Grandsire, Stedman, and Erin have a language of their own which I won’t be covering here! ↩︎

If it helps to hear it another way: the calling position is not named by where the observation bell is when the call is made; it’s named by where the observation bell is when the call has been executed, which is a whole pull later! ↩︎

There is another call known as “Middle” that we won’t cover in this section, but it can also be abbreviated with M. Often when there is a Middle (M) calling position available, the calling position used for making the fourths will be simply Fourths (F). ↩︎

It came up in the process of compiling this section that in fact, the two calling positions “Wrong and Home” used to be known as “Wrong and Right”. Conducting is definitely a living tradition and it has changed over time; clearly nothing here is set in stone! But I am setting down what I believe to be common practice these days. ↩︎

Technically, there’s also “Home” for when long fifths are made, but this is more often just thought of as being unaffected! ↩︎