Less Common Calling Positions #

As we discussed in the previous section, you can do a lot with a little; knowing only a few calling positions can enable you to call a good number of touches. However, to unlock the rest of the huge treasure trove of compositions that exist, it’s necessary to know just a few more things. In this section, we’ll cover:

- A few more common calling positions (enough to get you through a majority of commonly-called compositions)

- A common touch, used for practices or Sunday services, that uses some of these new calling positions as well as some familiar ones.

- A few resources you can use to teach yourself more calling positions, when it becomes relevant.

A few more calling positions #

In the first section where we talked about calling positions, we discussed the calling positions of Plain Bob Minor. Today, we’ll talk about two more calling positions which don’t exist in Plain Bob Minor, but do exist for Plain Bob Major and the majority of other methods on 8 or more bells.1

Brief review #

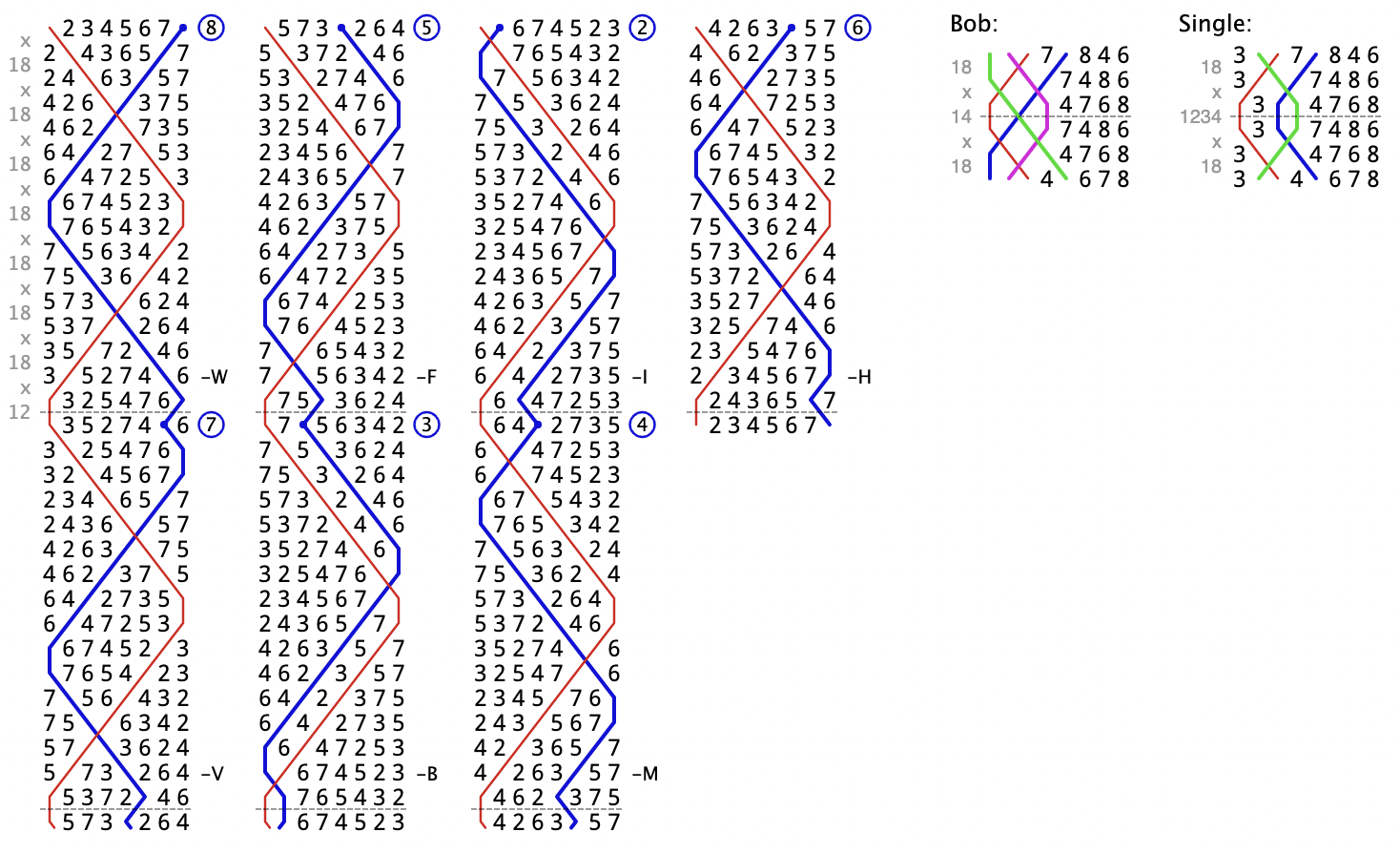

From Demystifying ‘In, Out, Make’, you should remember the Wrong (W) calling position, which comes after the first lead in Plain Bob. You can see it marked above as “-W,” right at the row where the call Wrong would be made. The Home (H) calling position comes after the last lead in the plain course, when the tenor is about to come to its home position (here, 8ths place) at the lead end. Note that Wrong and Home are farther apart from each other in Major compared to Minor because the calling positions are relative to the position of the observation bell (most often the tenor) rather than being, say, a certain number of leads in.

In between “-W” and “-H” there are several new symbols, laid out in the table below:

| Calling Position | Abbr | Definition (with tenor as observation bell) |

|---|---|---|

| Fifths | V | This calling position uses the Roman numeral for 5 to show that it is where the observation bell becomes 5ths place bell at the lead end. It is not very commonly used. |

| Fourths | F | This calling position marks where the observation bell would make fourths during the call (whether bob or single). |

| Before | B | At a Before, the observation bell is coursing before the treble and ends up either running out at a bob or making seconds during the single. |

| In | I | At an In, the observation bell will run in during a bob. Note that if there is to be a single called at this place in the blue line, this calling position is sometimes called Thirds (T). |

| Middle | M | Beware, this is M for Middle and not M for Make! More on this calling position below. |

Extra considerations #

More about Middle

Middle is an extremely commonly used calling position, but it is a little trickier than some of the others. The name is not obvious unlike “In” or “Fourths,” yet it’s used in a huge variety of compositions. For even stage methods, like 8 or 10 or 12, Middle most often refers to the time when the observation bell becomes the place bell two less than the number of bells ringing. So, if Major is being rung, the Middle is called when the observation bell becomes 6ths place bell. If Royal is being rung, the Middle is called when the observation bell becomes 8ths place bell, and so on; just subtract two from the stage.

For odd stage methods, the definition of Middle can be confusing or inconsistent, so it’s very important to make sure that you are aware of what the composer intended.

Which of these calling positions are the “most important” and why?

In the table above, only Fifths, Fourths, and Middle are technically “new”. Before and In were covered in the previous section on calling positions. If you are only going to learn one of the new calling positions at a time, Middle is the one to focus on first.

Why? It’s used in a huge variety of compositions. In my experience, knowledge of only Home, Wrong, and Middle will allow one access to a huge array of touches, quarters, and even peals. Okay, I hear you ask, but why those three?

To answer this question requires a bit of a tangent, so feel free to skip this bit if it doesn’t interest and go straight to the practice touch. Here are some reasons that Home, Wrong, and Middle are some of the most common calling positions. I’ll use the traditional notion of the tenor as observation bell to explain some of the reasoning, much of which is either historical or musical:

- Wrong, Middle, and Home (in methods where the lead end has a bell making seconds) are often situated in the course such that the observation bell (again, traditionally the tenor) will be unaffected by the call. That means that the observation bell keeps doing what it’s doing and doesn’t have to be involved in making the call.

- The tenor being unaffected is also desirable because the call therefore maintains the natural length of the course. If the tenor has to run in or make fourths or what have you, it veers off its normal path and the course may become longer or shorter (depending on the exact call and method). Recall that a course is commonly defined as the time between when the tenor is at its home position and when it returns there.

- You may note that there is one other calling position in Major which leaves the tenor unaffected; that is Fifths (V). The Fifths calling position, in contrast, is much less commonly used. Why? This has to do with some of the musical qualities guaranteed by using Wrong, Middle, and Home. Wrong, Middle, and Home happen at places in the Plain Bob Major blue line that don’t affect the tenor (the 8), but unlike Fifths, they also don’t affect the 7. Leaving the 7 unaffected is nice for stability (since ringers are so used to it), but it’s not a guarantee or a necessity.

- There is also a large element of tradition. A lot of work and time has been spent figuring out compositional structures involving Wrong, Middle, and Home, and they are building blocks used by many, if not most, composers. Ringers, conductors, and composers alike are used to many commmonly-rung compositions being “tenors together,” which refers to a composition where the tenors are always coursing each other. Even if you’ve never heard of “tenors together,” if you’re musically sensitive it’s quite possible that the music of a touch with “split tenors” would sound strange to you. Many subconscious assumptions about how a piece of ringing “should” sound, when violated, can lead to confusion and disarray even in otherwise strong bands, and so there is a tendency towards having most compositions remain tenors together.

A practice touch #

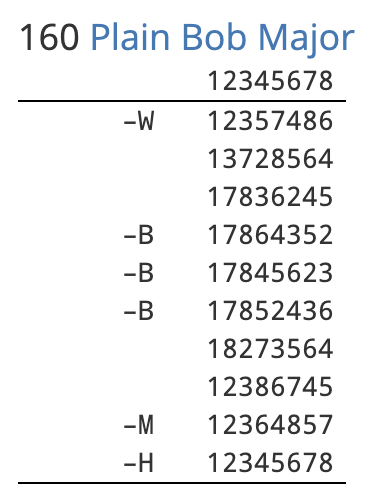

This practice touch will have you using some calling positions that should be familiar and some new calling positions. And no rest for the weary; I’ll be showing you the composition in yet another type of notation. Calling and conducting resources use a huge variety of (sometimes extremely) condensed notation. Much of it is fairly standardized by this time, but it’s my aim to show you a smattering of the types of notation you might see out “in the wild” when trying to find your own compositions. This next notation is most frequently used for shorter touches (less than quarter peal length), is extremely condensed, and relies on your new skills in remembering calling position abbreviations. Ready? Here’s the touch:

W3BMH

A common way to say this aloud is “Wrong, Three Befores, Middle, and Home”. Note that the 3 refers to the number of calls at Before — and not to anything else.

Different people will have different impulses when they are given a composition in this form. Some are very confident and feel ready to grab hold and try it right away. Some feel intimidated by the number of different calling positions and may be timid to try, especially if many of the calling positions are new. If you’re closer to the feeling-intimidated side, or even if you’re not, here are some tips that you can use whenever you see a new composition and you want to figure out how to crack it. Compositions are a little bit like mini-puzzles (which is, I suspect, why there is a high overlap between composers and puzzle-lovers) and it takes everyone a different amount of time to figure out how they best like to solve them. Here are some strategies that have worked for me; maybe they’ll work for you.

Strategy 1: Write It Out #

Maybe in the modern age this is a bit old-fashioned. After all, what are iPads for? But I think when you’re first starting, writing out and taking the time to go slowly through the touch and understand where all the calls are can be very useful indeed. Write out as much or as little as you need. You may start by writing out every single row, from rounds back to rounds! Or you may only need to write out lead heads, or another helpful schematic. But if you can’t figure out where to get started on a composition, writing it out is always a great starting place. Make sure you clearly understand where the calls go in and what they do to the bells; both your bell(s) and everyone else’s.

Strategy 2: Look It Up #

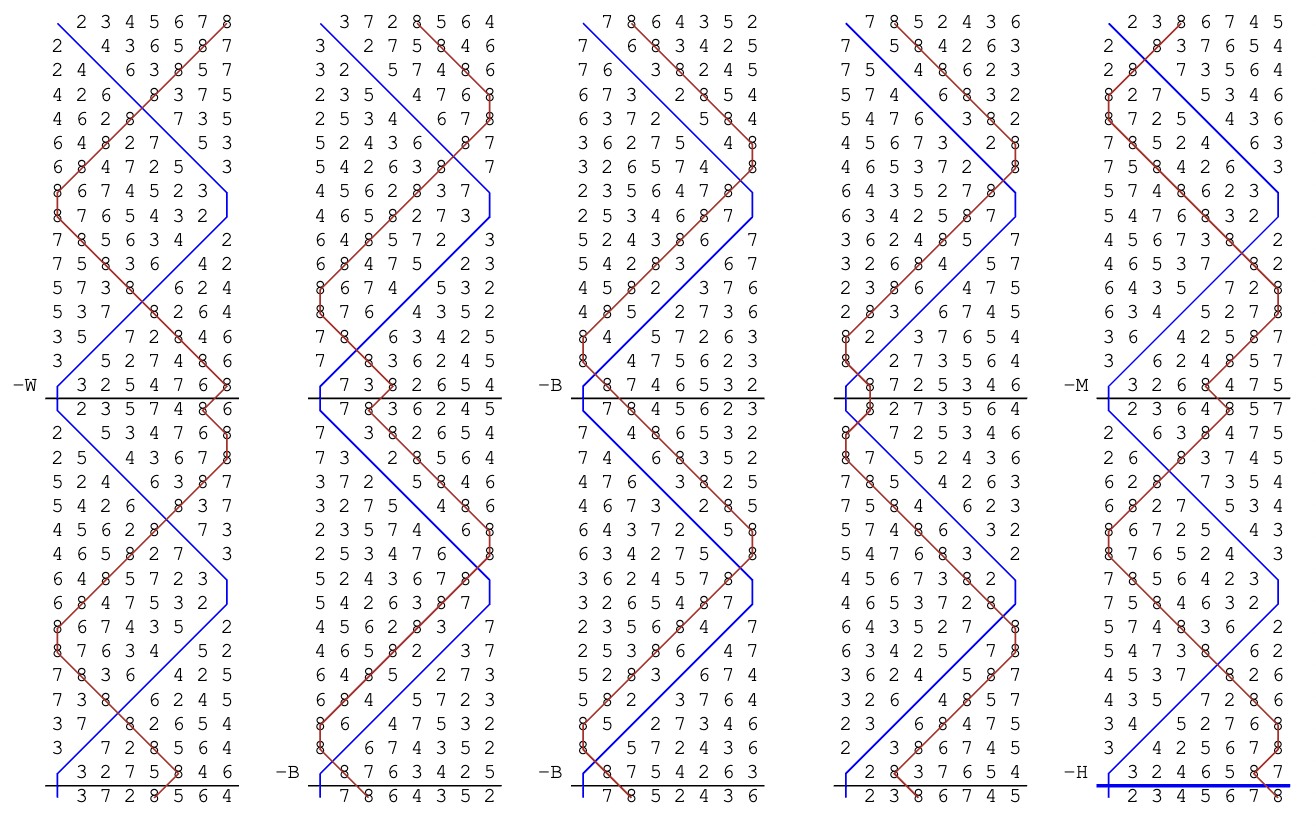

Graham John’s Composition Library is a huge boon for ringers everywhere, and it is an especially invaluable resource for the conductor (at any stage of their development!). If you’ve got a new composition you’d like to figure out, try finding it on complib (or, try inputting it yourself!). Here is a link to W3BMH. Click the gear button to adjust viewing settings. Do you like to view it by courses or by leads?

Of particular use, I think, is the “Blue Line” section, which can be expanded by clicking on the words “Blue Line” in the CompLib page. There, you can see each of the rows in the touch, written out, with a marking by where the calls ought to go. Note that the calls are written next to the row of the treble’s handstroke lead, and are written on the left-hand side rather than the right as in the image of Plain Bob Major above; this is just down to different people preferring different conventions.

The blue line layout is very useful for this touch. It can warn you that the 3 calls at Before all line up right next to each other! Since the tenor runs out at each call, it repeats the lead it just rang and is ready to run out again at the very next lead end. The call at Middle is just before the call at Home, and the “That’s all!” comes just as the final bob is executed! So there’s a lot happening at once. But it’s a beautiful touch, very musical and reasonably short, and great practice for these four common calling positions.

Strategy 3: Give It A Go #

Sometimes, there’s nothing for it but to give it a go. See if you can input the touch into your favorite ringing software and practice giving the calls in time. Or maybe you have a band all willing and waiting for you to call something new!

Resources for learning more #

You’ve learned most of the major (ha) calling positions! This is no minor (ha) feat. But of course, there are more calling positions than just those (especially if you include Grandsire and Stedman!); how is anybody supposed to keep track?

If you are needing to learn a new calling position, it’s likely because you have found or have been given a composition to learn that has a new-to-you calling position in it. Depending on how it is notated, it may or may not be obvious to see where the observation bell is in the lead head after the call is made. However, you have a few options for recourse: you can ask a band member or mentor, or you can look up the calling positions either in John Harrison’s Glossary or on Composition Library in the Help at the very bottom. Other resources may exist as well; please contact me if you’d like them linked here.

Exercises #

Answer this #

For the questions below, assume Plain Bob Major with the tenor as observation bell unless otherwise specified.

The tenor is dodging 5-6 down at the lead end (in other words: it will be 6ths place bell). What is this calling position called?

A bob is called at the Before calling position. What does the tenor do?

Practice this #

Try out the practice touch above. When you’re finished, reflect on what went well and what could’ve gone better. Sometimes it can be helpful to discuss with another band member or write it in a personal journal to keep track of areas for improvement. No one is perfect right away! The difference between progress and stagnation is looking for growth areas.

Find this #

Find a touch, either online or in print, that uses Before or Middle. Try the three stragies: write it out, look it up, give it a go. What works best for you? What order do you prefer to try the strategies in? Do you have other strategies that work well for you?

Notes #

Though, as before, the calling positions may mean slightly different things from method to method, or may come in a slightly different order! For example, in Kent Treble Bob Major, the Home comes after the first lead in the course. ↩︎