Checking the Ringing #

The ability to check the ringing is often thought to be the key difference between a caller and a conductor. In this chapter on Conducting, we’ll talk about tracking and checking the ringing, using information that you can get from the composition itself and doing some study beforehand.

This first section is on checking the ringing, and it focuses on how to use memorization and other skills you already have to check the ringing, without the use of coursing orders.1

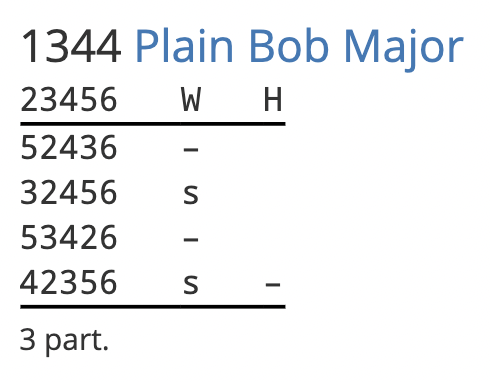

When learning to check the ringing, it’s often useful to start by studying the composition a little. The key is learning your landmarks and finding places where you know you can check that your ringing is accurate so far. I will focus on a few different landmarks that you can use to check the ringing as it’s going. I’ll use an example example of a quarter peal of Plain Bob Major.

Landmarks #

Landmark: Fixed bells #

The composition is laid out with each course displayed as a line. At the end of each course, the 6 is at the “end” of the line and the 7 and 8 are nowhere to be seen. This is by convention; since the 7 and 8 are unaffected, they are not written out in this style. So you can imagine a little “78” tacked on to the end of each of those rows. You’ll note the treble is also omitted, for similar shorthand reasons. In this composition, then, you can see that the 6, 7, and 8 remain end up at the same place at the end of every course.2 So, at the end of every course, you can check those three bells and make sure they are in the right place. Every other course, the 5 is also back in its usual position.

Landmark: Parts #

Another useful feature of a composition to watch for is the “part end”, which is the last row written above.3 That row will come up after the end of the first part. Here, it’s 42356 (again, imagine the invisible 78 at the end) which signifies that the 5678 are in their home positions, and the 2, 3, and 4 are swapped about at the beginning. I won’t get into details about how to derive later part heads, but I’ll just tell you that after the second part you’ll get 34256 and after you’ve rung three parts you’ll come back to 23456 (rounds!). Memorizing the order that the bells should be in at the end of the part means you have a couple of landmarks partway through the composition where you can always check to make sure the ringing is accurate, even if you can’t yet manage to track it all the time.

Landmark: Plain course #

If you didn’t ring (nearly) an entire plain course at the beginning of a composition, the remaining bits of the plain course often come up in the middle or at the end of a composition. Often, your ear will tell you when you’re in the plain course. Maybe the other ringers will smile at each other, wondering if this is going to be the end! You can also use these leads as landmarks. For example, in the quarter peal composition above, you enter the plain course again after the second “single” at Wrong. Then, just when it seems about to come round, it’s time for a “bob”!.

Other landmarks #

In a quarter peal or peal of minor, watch for it to come round (at least twice!). Watch for “roll-ups,” especially on high numbers. Know who’s making the bob, or involved in the single. Maybe knowing what happens at every call is too much, but you can still learn a few key ones, like at the end of a part.

If you’re particularly good at memorizing, you can also memorize any other aspect of the composition that is useful to you, like the course heads for example.

Eventually you can build up to using coursing order landmarks, and from there up to using the coursing order the entire time during ringing — but there’s no reason you can’t use these other strategies, too!

Checking it live #

Of course, there is a limit to how far studying can get you. Sometimes things can go wrong that you can’t anticipate or necessarily easily prepare for in advance. However, there are a couple of different techniques you can use for checking on the ringing as it’s going.

Give structural hints #

For bands that know the method well, giving structural hints can be a great help when something has gone wibbly. For example, stating when the lead end is or the half lead is can often give stability to a method that has been a little shaky.

Certain methods also have bits where it is easy to go wrong, and often conductors will mention them if the ringing has been unsteady. For example, in Kent Treble Bob sometimes people will forget whether to dodge or hunt; simply stating whether the handstroke/backstroke pair is a dodge or a hunt will often fix the problem. Or the ringers may forget about the Kent 3-4 places, in which case a quick “Places!” will fix it. In Stedman it is common to forget to finish one’s last whole turn. In London Surprise Major, mentioning where the fishtails in the back go (treble’s dodge in 3-4) can be very useful. And so and and so on — if you don’t know the common places for trips in a method you are conducting, see if you can ask someone about it in advance.

Watch the social cues #

Body language and social cues can be a valuable tool for conducting. While these days it is no longer a given that you are able to see the faces of your fellow ringers, when you are fortunate enough to be ringing as well as seeing the faces of those you are ringing with, they can be a great aid to your conducting. Sometimes it is possible to tell which ringer is lost by the position of their shoulders, or by the look on their face! Then, if you can see a “hole” in the ringing using your rope sight, it’s possible to set them into the right place.

For some conductors the process of giving structural hints and watching social cues is very instinctual. I admit it was instinctual for me, and I find it hard to describe this process and teach it in a useful way. However, I found it revelatory when Simon Gay wrote a series of articles on his blog about this type of non-coursing-order-dependent conducting, and I highly recommend you read them if you are interested in learning more. The two in particular I am thinking of are his article on structural conducting and his article on local conducting.

Whether you read those articles or not, I think one of the biggest determiners of whether these strategies are available to you have to do with how much ropesight you have. Building ropesight is so different for everyone; some people develop it nearly instantly and others struggle.4

But there are a few exercises you can try for building ropesight. First, watch as much ringing as you can. If you’re sitting out, watch the ringing. It’s a method you’ve watched a million times before? Try to pick out the coursing orders. It’s a method you’ve never even heard of, let alone knowing the line? See if you can quickly ask someone what the line of the treble is, and see if you can follow it up and down the changes. Or, see if you can tell which bell is ringing first or ringing last. These types of ropesight exercises can be practised at any level and will greatly aid your ability to see and react to what’s happening around you in the tower. Other people will have written much more on ropesight than I have time for here!

Summary #

These are a collection of strategies and tools you can use as a conductor. You may use all, or some, or none; but practicing using different techniques will make you a more flexible conductor, which I think is valuable in its own right (even if you decide not to use them often or at all in the end).

Exercises #

Write this #

Write down, in a journal, diary, blog post, or other venue (private or public), the types of tools you use when you are conducting. Are there any tools or ideas you’d like to add to this list? Think about how you can best get practice using these new tools.

Talk about this #

Ask around your local tower, your Facebook group, or other venues about how other people think about conducting. You’ll likely find that everyone has their own ways of doing things! By learning about a broad range of strategies, you are more likely to find one or more that work well for you.

Read this #

Read Simon Gay’s two blog articles on structural conducting and on local conducting.

Notes #

If the advice seems familiar, it might be because much of it is derived from an article I wrote for The Ringing World in 2020. ↩︎

Bells that remain in the same position at the end of a course or part are often called fixed bells. ↩︎

Recall that the “technically correct” term is the part head, but this term is mostly used in composing contexts; the vast majority of the time, the common usage “part end” is what you will hear about in practice. ↩︎

I remember one time at my local tower when a ringer’s uncle came by to visit. He had never rung before, and didn’t know anything about change ringing other than his niece’s enthusiasm. I sat next to him during a course of Plain Bob Minor and was talking him through what the treble was doing. He paused for a minute, and then asked me why the 5 was ringing after the 6 like that. Immediately after he asked me the question, a lead end happened (the 5 made 2nds) and he exclaimed “Now it’s changed!” and then described the new relationship between the 5 and the treble. He didn’t know the ringing terminology, but he had incredible ropesight and an instinctive ability to pick out coursing orders, which to this day I find incredible. I suspect his level of innate skill at picking out coursing orders is very unusual! ↩︎