Round The Circle #

In many resources about conducting, a particular emphasis is put on learning how to conduct from the tenor. This emphasis arises from a combination of long-held tradition and compositional convenience, but conducting from the tenor is not your only choice! This section of Calling It Round will spotlight different places in the circle from which it is possible to conduct.

Conducting from: the observation bell #

In many compositions, the observation bell is the heaviest working bell, and all of the calling positions are portrayed relative to its path through the blueline. It is common to conduct from the observation bell, especially as a beginning conductor.

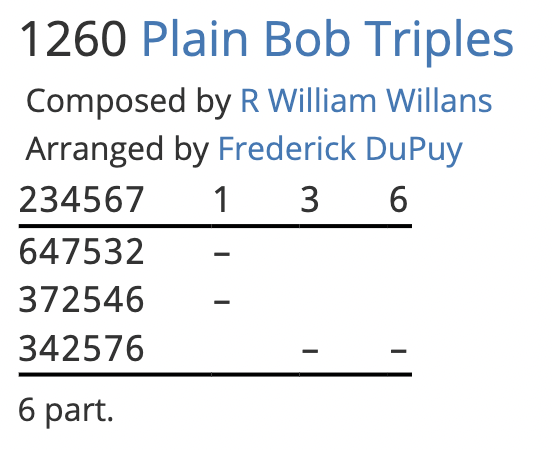

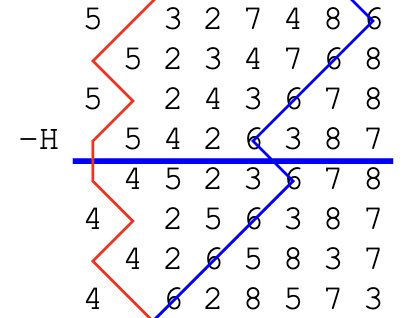

Sometimes compositions will be written out explicitly for other observation bells, but in my experience this is fairly rare. Often when the tenor is not intended to be the observation bell, no calling positions are given at all, and instead calls are shown at the lead number as in this composition, shown to the right. You’ll need to pick your own observation bell — or bells! A helpful strategy is to look at the part end1 and see if any of the bells end up in their “home” position at the part end, because then you know their work repeats in each part.

Here, you can see that only the 5 ends up in the home position at the part end, which is 342576. So, the 5 might end up being a wise choice for observation bell because it will do the same thing in all six parts. By contrast, the 7 (perhaps a more traditional choice of observation bell for a triples composition), swaps places with the 6 every other part. Still possible to memorize, but certainly harder work.

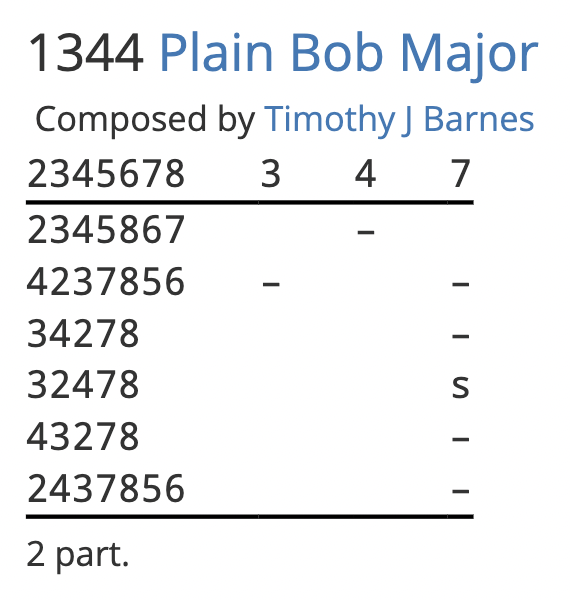

To make matters harder, often you have to puzzle the observation bell out for yourself. Or, it might change from part to part, such as in this composition shown to the left, where (depending on preference) it might make sense to use the 6 or the 8 for observation at different times. Note how the 7-8 pair and the 5-6 pair are “swapped around” at the part end! Ringing the first part with both 6 and 8 as observation, you can think to yourself: “Before for the 8, Before for the 6, then five Homes for the 6” (remembering that the 3rd Home is a single, not a bob). Then the second part is “Before for the 6, Before for the 8, then five Homes for the 8”. It’s very structured in ways that might not be obvious from the ink on the page, and quite a pleasure to ring (very musical too!).

Another option for this composition is to use the 2 as observation, since it does return to its home position at the part end. However, it requires you to use many more calling positions than just Before and Home for different bells! Different folks will find different strategies easier or harder. In some compositions, no bells return to their “home” position at the part end, and the problem of choosing the observation bell can be particularly evident.

Conducting from: the cover #

Conducting from the cover is not particularly often done,2 but I think it has a place in this section. There are all sorts of reasons to enjoy conducting from the cover, including in the early stages of learning calling and then again in the early stages of picking up coursing orders. It might also be preferable if the other members of the band really want to ring inside, for example. It is also marvelous practice for watching another bell be observation bell, rather than ringing the observation bell, which is a useful skill for the reasons outlined above.

Conducting from: the treble #

The treble is another great place from which to start learning to conduct. It’s often a great place from which to watch coursing orders, especially since you might not need to have as many brain cells concentrated on ringing the method. Similarly to the cover, you also get rope-sight practice watching the observation bell, but with the added challenge of ringing a bell that moves through the method a little more. Bonus: you always know when the lead end and half lead are.

It’s worth noting that eventually, conducting from the treble may feel harder than conducting from inside, especially on large numbers of bells. But lots of people do at least a little bit of conducting from the treble, and it can be great fun and good practice.

Conducting from: a “non-observation” bell #

While compositions are often written out with an observation bell in mind, sometimes (for whatever reason), you may prefer to ring with another bell as observation. For example, at my home tower the tenor is quite heavy and I’m not yet very good at ringing it cleanly. It’s a skill I’d like to build but it’s not there yet! So while I’ll conduct from the tenors in hand, I prefer not to conduct from the tenor in tower, generally. Therefore, I’ve developed a variety of strategies to avoid it!

I’m ordering the strategies roughly by what I perceive the relative difficulty to be, but others may find different things easier or harder.

Strategy 1: Watch the observation bell from elsewhere #

This strategy requires some ropesight and maybe some advanced preparation, but is generally fairly accessible. It is the same strategy you can practice while ringing the cover or the treble, but this time you will be ringing an inside bell while watching another inside bell as observation. It can sometimes be beneficial to figure out good “landmarks” for watching the observation bell during this time that will give you a bit of warning. This may require some pen-and-paper work figuring out what the tenor does at various lead ends or half leads, for example. If you don’t notice that the tenor is dodging the treble at the front until it’s happening, you’re already too late to call the Before!

Strategy 2: Take a lighter fixed bell #

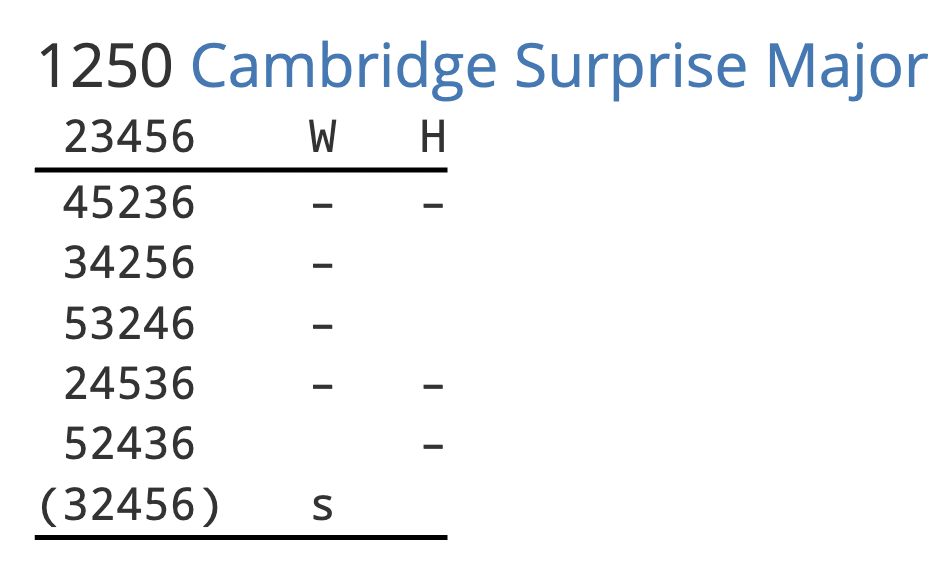

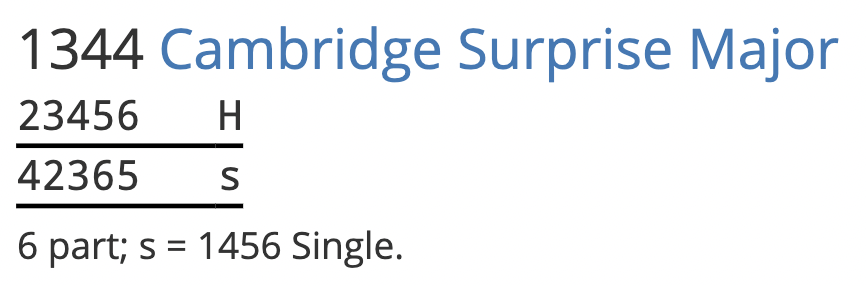

The strategy of taking a lighter fixed bell is sometimes easier said than done, depending on what bell or bells you consider light. For example, this 1344 of Plain Bob Major does not have a fixed 2, 3, or 4! So you either have to ring a heavier bell, take on a greater memorization burden, or use one of the other strategies on this list. But let’s say we’re wanting to ring the 6 at our 8-bell tower to this 1250 of Cambridge Surprise Major shown to the right.

You can see that there are only calls at Wrong and Home for the tenor, and that the 6 comes back to its home position at the end of every course. Since the 6 is therefore a fixed bell in this composition, it seems a good target for this strategy. The idea is to translate the composition from being tenor-based to being 6-based, so you can ring and use your own bell as observation, even though the composition was not originally notated that way. Using your own knowledge of Cambridge or using the blueline feature on CompLib, you can see that “Wrong” for the 8 is “Home” for the 6. (Phrased another way: when the 8 is dodging 7-8 up, the 6 is dodging 7-8 down).

Whereas “Home” for the 8 is “Middle” for the 6. (Phrased another way: When the 8 is dodging 7-8 up, the 6 is dodging 5-6 down.)

So for the 8, you could say the composition: “Wrong, Home, 3 Wrongs, 2 Homes, single Wrong”. For the 6, the same composition could be said “Home, Middle, 3 Homes, 2 Middles, single Home”. The only difference is that you are watching your own bell (the 6) using the calling positions relative to the 6 after you’ve translated them from “tenor-speak”.

This strategy does generally require some pen-and-paper work (or mental figuring) before you begin, but it pays dividends in that you can generally figure out a way to ring the bell you want to ring and the composition you want to ring, even if they seem initially at odds. And you don’t have to watch anyone else’s bell to figure out where to put the calls in (obviously you will want to watch to see if it’s going well!).

Strategy 3: Rotate the composition #

This strategy requires perhaps the most pen-and-paper work, but can be fun and a good exercise. I will cover only the general idea here.

Recall the touch of Plain Bob Minor that goes ppb ppb. We saw this touch in an earlier chapter of Calling It Round. It turns out that you can also call a very related touch: pbp pbp. And another: bpp bpp. These touches are so related to one another that many ringers would call them rotations of a single touch. To understand a little more about why, it’s useful once more to shed our limited linear writing system and look at a circle:

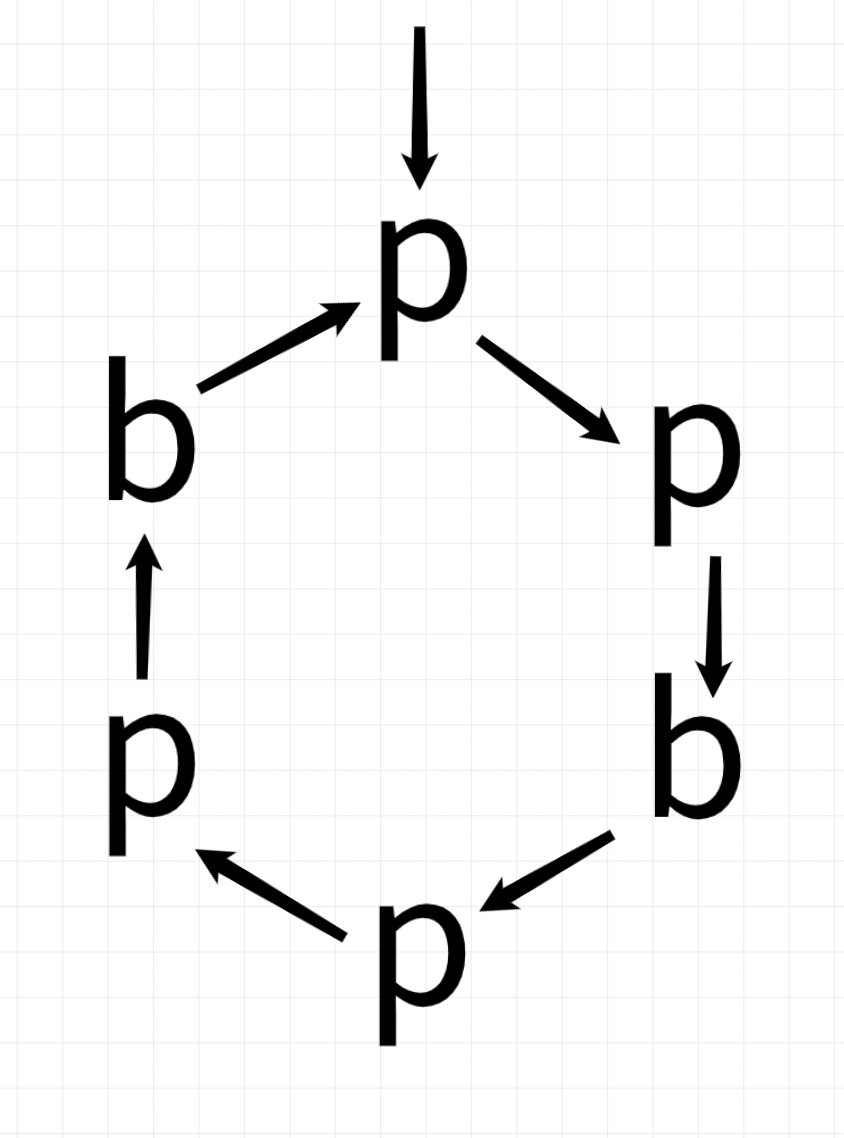

Around the circle are all the plains and bobs in this touch. In ppb ppb you start at the top:

But you can also start in the middle:

Or anywhere else:

It doesn’t matter where on the circle you start — plain or bob, top or bottom, whatever — the idea is that ringing a bob and two plains around the circle like this will always get you back where you started.

This feature of compositions extends to more complex compositions. Often when you rotate a composition, different bells become more or less reasonable to use as observation bells.

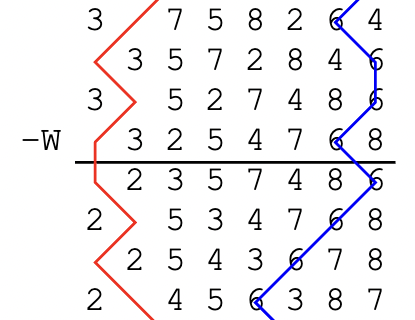

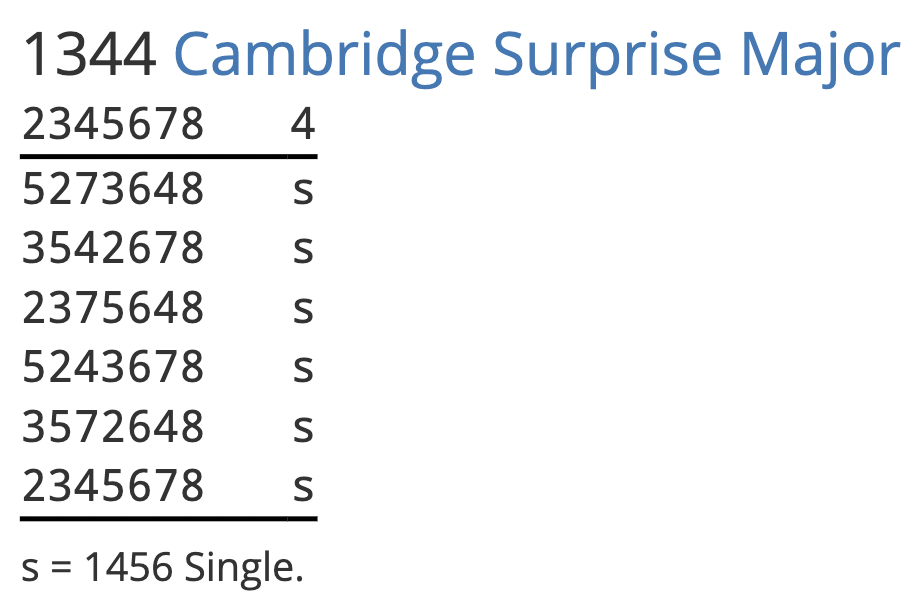

I will show one example of rotation of a slightly more complex rotation. Here’s a 1344 of Cambridge Surprise Major. Note that the definition of a single is not 1234 (so probably best to warn your band before ringing!). The composition has you ringing a single at Home (for the tenor) every course for 6 courses in total.

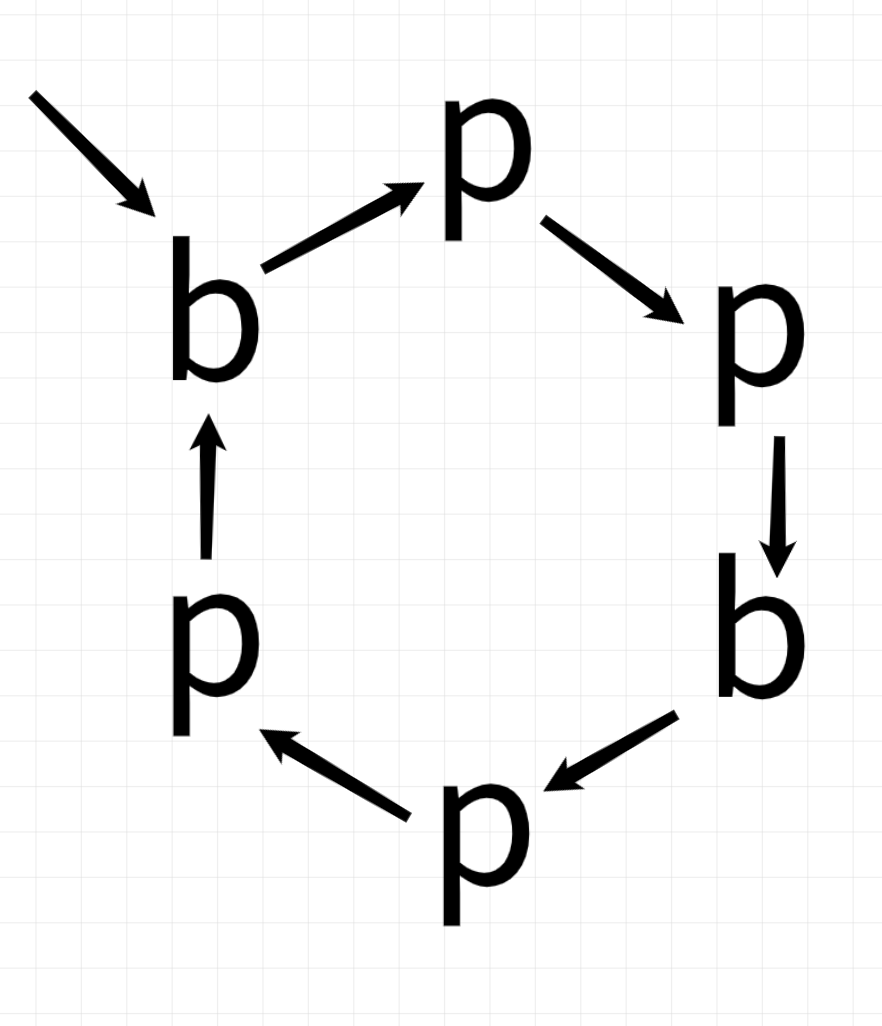

Writing this out by-the-lead, we know that Cambridge has 7 leads per course and we get: pppppps pppppps pppppps pppppps pppppps pppppps. Or more succinctly: pppppps, 6 part. Just like with the short composition of Plain Bob Minor above, you can rotate the singles to happen anywhere in the composition. Let’s try looking at what would happen if you put the single somewhere in the middle: pppsppp, 6 part. You get the following rotation (the “4” at the top just means the 4th lead in the course gets the single).

Let’s take a closer look. Before, the 7 and 8 were fixed (we know this because the 7 and 8 were omitted from the part ends). Now, different bells are fixed. One fixed bell is still the 8; you can tell because it’s at the end of every course head, in its home position. What is the other fixed bell?

You can rotate it several different ways to find a rotation that works for you and has a fixed bell you like.

Warnings:

- While this strategy will never lead to falseness (if the original composition is true), it may drastically change other aspects of the composition, such as musicality. Beware!

- If you are using software to rotate compositions rather than working them out yourself, be careful that it is doing what you want. For example, in CompLib if you ask it to put the single in the 3rd lead in every part, it will happily do so; however, the single affects the tenor which causes the course to be lengthened. So the next single comes in the 3rd lead of the next course, but does not come exactly 7 leads after the first, which violates the rotation rules and, in this case, leads to falseness.

- You cannot use this strategy to get arbitrary fixed bells. There is a simple mathematical proof of this fact. There are 21 different pairs of working bells (7 choose 2). There are 7 different rotations, so you can at most see only 7 of those pairs fixed. So for any given composition, you may not be able to get the 2 fixed, or the 3 and 4 fixed, for example.

Strategy 4: Coursing orders #

This strategy is, to my estimation, more involved than the above options. It requires you to be able to figure out a way to watch the coursing order from your bell, wherever it may be, and then figure out how you want to change the coursing order and then make that call at the appropriate time. I think this is somewhat beyond the scope of this section, but I wanted to make you aware that this is an option and many of the best conductors I know use it to conduct from anywhere in the circle.

Conducting from: a handbell pair #

If you’re particularly interested in conducting for handbells, I recommend reading the Supplemental Skills section on Conducting in Hand.

Notes #

Yes, technically, the part head. :) ↩︎

I checked BellBoard for the number of times a tower bell performance of Triples had been rung with the conductor on the cover. There were over 300 performances; so while not common, it’s not particularly rare either and generally several quarters or peals are rung this way each year. ↩︎